Return to Dynasties of Sargon (Old Akkadian), Ur-Baba (Lagash II), and Ur-Namma (Ur III)/Biographies

Amar-Suen

Go here for the year names of Amar-Suen

click here for CDLI Royal & Monumental entries for Amar-Suen

Go here for all the texts dated to Amar-Suen on CDLI

Amar-Suen (2046-2038 BC)

Although Amar-Suen succeeded his father Shulgi (2094-2047) and ruled as the third king of Ur III dynasty for a period of nine-years (2046-2038), little is known about him. He is not mentioned in economic texts that date to his father’s reign, and the only documents that specifically mention Amar-Suen by name and that date to his reign are building inscriptions (Michalowski 1977:155).

Amar-Suen in Ur III texts

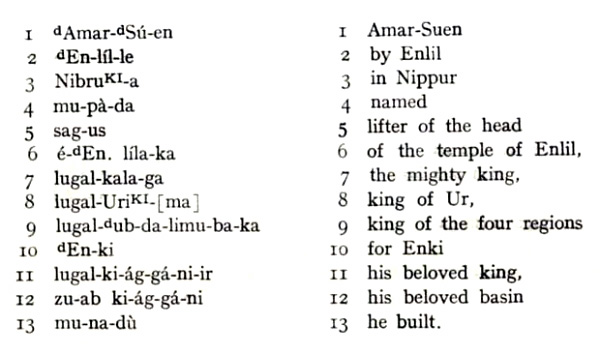

This brick inscription (ca. 1998-1989 BC) follows the standard literary formula for building inscriptions that consists of several lines of epithets and a description of a building or monument that the king commissioned in honor of the god(s). In this text the god Enlil sanctions Amar-Suen’s rule, and he is credited with building a basin for the god Enki at Nippur. Matouš suggests that this basin (referred to as an abzu/zu-ab in the text) was a temple basin that was filled with water and was a symbol of the junction of the physical world and the deep waters of the underworld (Matouš,1962, 3)

Bibliography

- Matouš, L. "The Inscription of Amar-Suen". 1962.

- Michalowski, Piotr, "Amar-Su'ena and the Historical Tradition, in Ellis, Maria de Jong (ed.), Essays on the Ancient Near East in Memory of Jacob Joel Finkelstein (Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts & Sciences, 19), Archon Books: Hamden, Connecticut 1977, 155-157: score transliteration, translation, commentary.

Amar-Suen in Old Babylonian Texts

I. Ur III Royal Correspondence

During the Old Babylonian period (1800-1595 BC) scribes copied and archived the royal correspondence of Neo-Sumerian kings in order to preserve the memory of the Ur III dynasty. The letters and royal documents of Shulgi, Shu-Sin, and Ibbi-Sin were meticulously copied, however, the royal correspondence of Amar-Suen was not included in this collection of texts. He only is referred to twice in letters from his father Shulgi’s correspondence in connection with the maintenance of an irrigation system in the Karkar region, and the manumission of slaves (Michalowski 1977:155). Although these two letters do not provide much information about Amar-Suen’s activities during his father’s rule, the scant evidence suggests that he held an administrative position.

II. Amar-Suen in Old Babylonian Literature

Old Babylonian scribes also copiously preserved and copied royal hymns of all of Ur III kings with the exception of Amar-Suen (Michalowski 1977: 155). While these hymns are an excellent source of information concerning the other Ur III kings, they do not mention Amar-Suen. There are two possibilities for the omission of Amar-Suen from the Old Babylonian archives of Ur III royal hymns:

- Amar-Suen left no legacy of royal hymns composed in his name.

- Old Babylonian scribes censured the royal hymns that were composed in his honor.

The two Old Babylonian literary texts that refer to Amar-Suen narrate how he is unable to rebuild the god Enki’s temple. The passage from UET 8 33 indicates that although the temple is in ruins, each year that Amar-Suen attempts to renovate it, he fails. This cycle continues for 8 years until the god Enki intervenes and finally in the ninth year of his rule, Amar-Suen builds an “oven-temple” for Enki (Michalowski 1977: 156). The term “oven-temple” Enki’s temple at Eridu which is described in religious hymns as being a place of abundance “where the oven brings bread”. These two texts provide a time frame for Amar-Suen’s reign. Out of the nine years that he rules, Enki only allows him the commence work on the temple during his last year as king. It is important to note that this text implies that the god Enki hampered Amar-Suen’s efforts to renovate the temple. The second year that Amar- Suen fails to rebuild the temple he dons a mourning garment as a symbol of his piety in the hopes of pacifying Enki. Amar-Suen also makes the effort of commissioning a “master craftsman (line 15), and of searching for the “ground plan” or foundation of the temple. Although in the end Enki relents, in these two O.B texts Amar-Suen is characterized as having been snubbed by Enki for the most part of his reign.

Gudea Cylinders A and B (2100 BC) indicate that by the time of Amar-Suen’s rule, religious traditions associated with temple rebuilding were already established. It is clear that the king had to fulfill certain religious requirements before the actual temple construction could take place. These narratives place great importance on the caution and diligence with which the king should adherence to the “temple rebuilding” rituals. It is clear that in order for a temple renovation project to succeed the king had to ensure that it was mandated and sanctioned by the temple god. King Gudea is very careful to consult oracles before he undertakes the rebuilding of the god Ningirsu’s temple. Gudea provides the god with many sacrifices and offerings, and he attempts to purify the city by expelling the sick and the “unpleasant to look at” from his city . These descriptions of the process of temple rebuilding indicate that temple rebuilding was viewed as being a very dangerous endeavor and should be proceeded by consulting oracles, sacrifice, and ritual purification.